Women's March for Peace

When the CPT team arrives at the door of Ashti Khan, we receive a warm Kurdish welcome, as is customary—affectionate greetings, a seat in the lounge room, and offers of tea, water, and fruit. Once the formalities are over, we get to the reason for our visit: we want to hear some extraordinary stories from Ashti Khan’s life.

When Ashti was a young woman barely out of her teens, she was arrested by Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime. Her charge was being a member of a Kurdish independence organization. Her sentence: 15 years in Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad. She was the only Kurd in the prison, alongside 45 Arab women—Shi’a political prisoners who had also opposed Saddam’s government. Her ethnic isolation was a political tactic, meant to break her spirit. It didn’t work.

“Our beliefs in freedom kept us strong. I had a lot of self-belief. It’s the only way to survive.”

She adapted to prison life by building friendships with the other prisoners.

“I was Kurdish, they were Arabs. I was Sunni, they were Shi’a. I was a communist, they were Muslims. I had to adapt. If we were going to survive 15 years in prison, we had to get along.”

After three years, a Kurdish uprising on the outside led to a prisoner swap. She returned to a Kurdistan that had gained some autonomy and began studying to become a teacher.

It’s an incredible story—one that reveals both Ashti’s strength and a chapter of Kurdish history. But we have also come to ask her about something that happened a few years later: the two main factions of the Kurdish independence movement turned on each other in a bloody civil war.

Over 5,000 people would die in that war—including Ashti’s brother. In May 1994, after hundreds had already died in the early months, a group of women decided it was time to take dramatic action for peace.

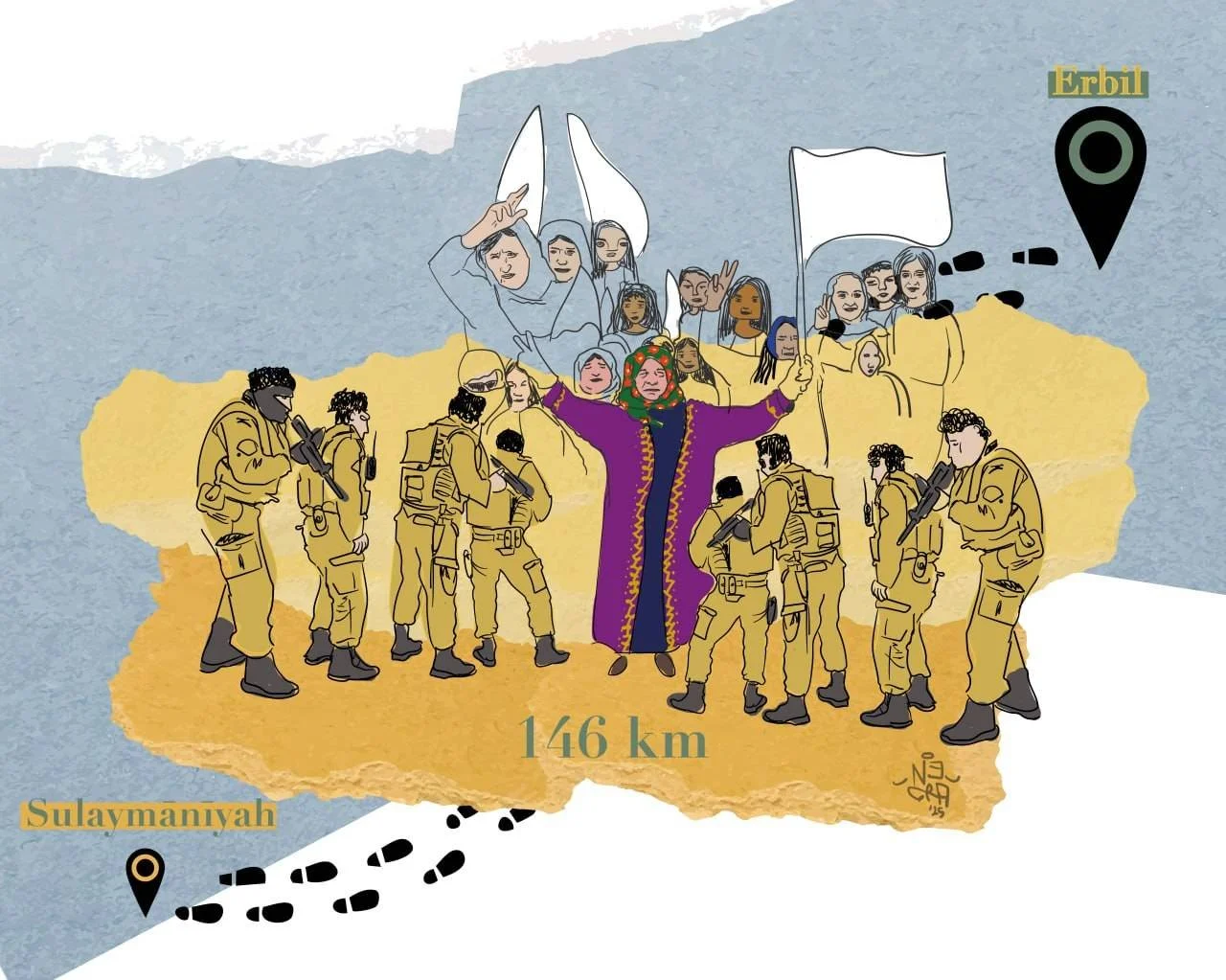

They organized a women’s march—walking from the base of one warring party in Sulaimani, almost 200 km to the base of the opposing force in Erbil. The aim was to send a message to the Kurdish people and the international community:

“We want peace.”

The walk was the brainchild of Ashti’s aunt, Jamila Khan—“an amazing intellectual and educator.” She invited all women who believed in peace and freedom to join her. During the resistance to Saddam Hussein, women had supported guerrillas in the mountains. But now that war had turned inward, against fellow Kurds, these women decided they had to intervene. Their political inspiration was the sacrificial love of a mother—to go to the frontline not to kill, but to risk their own lives for the safety of others.

Jamila came to the family home to talk about the walk. She warned that they might be arrested or killed—so only those willing to face that reality should join. Other women were told the same. The walk would be long, they would be camping along the way, and they would bring very little food. If anyone had health issues or doubted their strength, they were asked not to participate.

In Ashti’s house, feelings were mixed. Ashti herself wanted to go but couldn’t get time off work. Her mother was determined to join. Her brother supported the march—he had lost his own brother in the war. Her father, however, traumatized from the conflict, didn’t want anyone else in the family to risk their life. But he was powerless to stop his wife.

The women gathered in the public garden near the Sulaimani bazaar. There were 40 to 50 women, all over the age of 45. Ashti came to the farewell, sad she couldn’t join. A crowd gathered for an emotional sendoff. The women said they would walk along the highway, carrying white flags for peace, and if anyone tried to stop them, they would not turn back.

“There were many challenges,” Ashti tells us—a clear understatement. It was early summer, with temperatures climbing above 40°C. The mothers and grandmothers wore traditional Kurdish clothes and simple shoes or sandals. They carried only some bread and snacks they had baked, taking just a few bites each day.

For almost two weeks, they walked—hungry and thirsty, stopping each night to massage each other’s sore feet. At one point, two women became very ill with severe gastro symptoms. A third woman accompanied them back home.

When the women reached Erbil, they were met by security forces and members of the opposing PDK party. The men shouted insults. Jamila Khan stepped forward to confront the soldiers. They abused her and slapped her.

At that moment, the women believed they might not return home alive. Soldiers blocked their path. But the women walked on, insisting it was a nonviolent march and they would not stop until they reached the parliament. The soldiers hesitated—culturally, they had been taught not to harm a mother. After a tense standoff, the blockade parted. The women continued toward the parliament.

They had chosen the parliament as their destination, rather than the headquarters of either political faction, because it symbolized democracy and Kurdish unity. They wanted a neutral place—to send a message to sons and husbands in the PUK as well as those on the other side of the conflict.

When they arrived, security forces fired a volley of bullets over their heads. Once again, the women feared they would be shot. But they linked arms and kept walking—right into the parliament, where they delivered their message of peace.

It’s hard to imagine what they felt at that moment. These women had endured so much—two weeks of walking, decades of war and oppression. They had risked everything for peace, a desperate plea for their nation to do the same. And in reaching their destination, they proved that even the most improbable goals can be achieved if you truly believe in them. Maybe even peace in Kurdistan was possible.

After a few days in Erbil, the women returned to Sulaimani—this time by car. The villages along the road, unsure at first what to make of them, now welcomed them with cheers and waves, having heard of their courage.

Soon after the march, a temporary ceasefire was declared. Unfortunately, the civil war continued for years, with many failed attempts at peace. It remains a period of history that many Kurds are ashamed to discuss. As a result, the story of the women’s peace march is not widely remembered. Most of the women who participated have passed away, and even the two photographs taken—one before they left Sulaimani and one upon arriving at parliament—appear to have been lost to time.

But the legacy of those courageous women endures. I ask Ashti Khan how she feels when she looks back on it all.

“I feel sad and full of regret that I missed the opportunity to be part of it. But I feel very proud of them. It’s a very beautiful story. Please write about it—people today need to hear these stories so they can learn from them.”

So, I wrote the story down.

The memory of war is everywhere in Iraqi Kurdistan. It’s in monuments and museums, but also in the physical and psychological wounds of its victims. In the grief of families who have lost—and continue to lose—their loved ones. It is etched into the land: scorched hillsides where forests once grew, landmines still lying in wait, and new craters left by Turkish and Iranian bombs and shells. The memory of war fuels grievances, revenge, and ongoing conflict.

So this is a story for the memory of peacemaking. Of incredibly courageous women who walked away from the battlefield and chose instead to risk their lives for the safety of others and the future of their country. Who tried new tactics when the old ones only caused more suffering. Who channeled their grief and anger not into more violence, but into a creative attempt to break the cycle. Who walked not just from Sulaimani to Erbil—from PUK territory into the turf of their enemy—but from a legacy of violence toward the hope of peace.